In the romantic comedy of the future, the protagonist won't have to dish about being depressed to a sassy best friend.

Instead, facial coding software recognizes a frown. The emotional distress protocol is activated. Soon, a pint of Ben & Jerry's ice cream is delivered via drone, while a movie starts streaming on the 16K TV.

Okay, so maybe that scenario isn't likely. But software that interprets mood and human emotion isn't science fiction — it's something that is being used, and marketed, at this very moment.

"It's happening now," Rana el Kaliouby, co-founder and chief science officer at Affectiva, an emotion measurement technology company, told NBC News. "I think people are a lot more open to turning on their webcam and I think there is an understanding that your facial expressions communicate emotion, and that technology can interpret that."

Research on facial coding started in labs around 15 years ago, el Kaliouby said, which included her work as a research scientist at MIT. Over the last few years — as webcams have become better, algorithms more sophisticated and computers more powerful — multiple companies have delved into making this technology more accessible, both to businesses and individuals.

Affectiva focuses on facial coding technology for market research purposes. For example, a TV network could track whether you are smiling and laughing during a sitcom and then use that information to sell advertisers on the fact that its viewers are engaged with a show, instead of napping or playing with their smartphones.

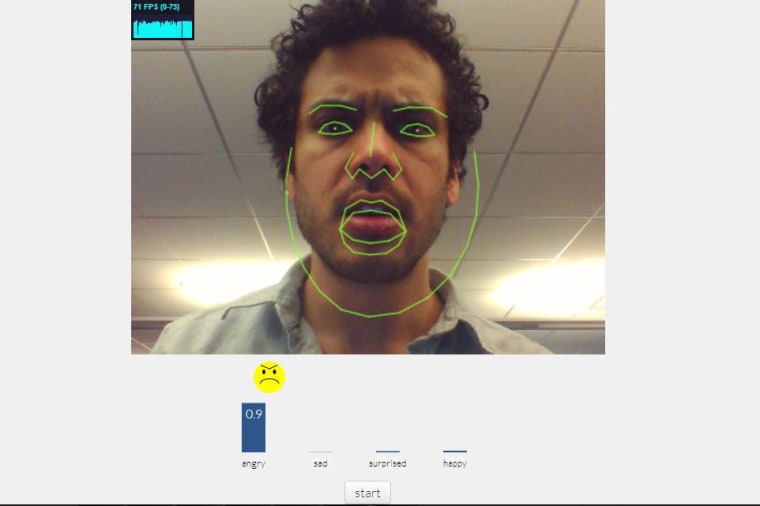

It's not only big companies that are playing with facial coding. Take clmtrackr, a Web app developed by Norwegian designer Audun Øygard (and the subject of a report in The Atlantic). It analyzes 70 points on the face through your webcam and interprets mood based on everything from the arch of the eyebrows to the shape of the mouth.

Then it rates how you are feeling, dividing emotions into four categories: angry, sad, surprised and happy. Obviously, that doesn't cover the vast spectrum of human emotion, but it provides a starting point for things like "mood journals" that could be used to automatically track someone's emotions or send weekly reports to someone's therapist.

Smaller apps like this could become more common once Affectiva releases its app developers kit. One company, called Portal Entertainment, has already used it to create a horror film recommendation service that sends you terrifying videos based on how scared you seemed during the last horror flick you watched.

Sension, based in Menlo Park, Calif., is also using facial coding, except that it utilizes Google Glass instead of a webcam or smartphone. Eventually, that kind of real-time feedback could help people with autism better express their emotions.

Sension's technology was also licensed to a company called MindFlash, which hopes to use it to train employees more effectively. For example, if a trainee looks bored, confused or distracted during a presentation, the software makes a note of it, hopefully allowing employers to make slightly less boring training videos in the future.

The key to making facial coding technology even more advanced is to increase the number of expressions that are scanned and stored. The more diverse the database, el Kaliouby said, the more programs can account for differences due to age, gender or race. Affectiva currently has 1.2 million videos to work with.

"The key is to show the program tons of examples," she said "With time, computers will be better at reading nuanced expressions, like a lip pucker or an eye squint. These kind of expressions are a lot harder for computers to read right now."

Keith Wagstaff writes about technology for NBC News. He previously covered technology for TIME's Techland and wrote about politics as a staff writer at TheWeek.com. You can follow him on Twitter at @kwagstaff and reach him by email at: Keith.Wagstaff@nbcuni.com