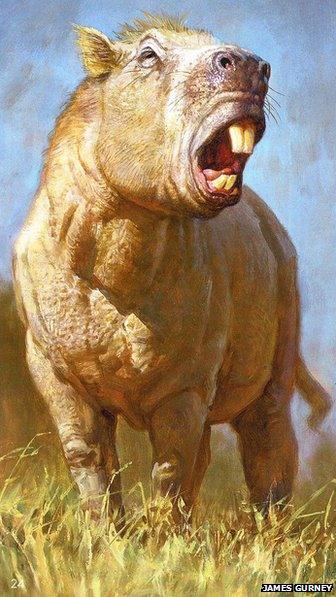

Biggest rodent 'fought with teeth' like tusks

- Published

Scientists say the largest ever rodent probably used its huge front teeth like tusks, defending itself and digging with them instead of just biting food.

The bull-sized cousin to the guinea pig died out around two million years ago.

Based on a CT scan of its skull and subsequent computer simulations, its bite was as strong as a tiger - but its front teeth were built to withstand forces nearly three times larger.

This suggests that its 30cm incisors were much more than eating implements.

Researchers from York in the UK and Montevideo in Uruguay published the work in the Journal of Anatomy.

Only a single fossilised skull has been found belonging to this 1,000kg South American rodent, known as Josephoartigasia monesi. Unearthed in Uruguay in 2007, the animal lived in the Pliocene period - a warm era when large mammals were relatively abundant, including the first mammoths.

It remains the largest rodent ever discovered.

To study the mechanics of the skull, the team performed a CT scan of the skull and used it to reconstruct a computer model - including its missing lower jaw, which they copied from a related species.

They then tested this model using "finite element analysis", a technique from engineering which calculates stresses and strains in complex objects.

The forces predicted during biting were large, and similar to a tiger's jaw. But the rodent's big incisors appear "overengineered" even for that sort of strain - and would probably stand up to much stronger forces.

So the researchers believe the front teeth must have been used for tasks that required extra muscles, like the neck, as well as the biting action of the jaw muscles themselves.

"We concluded that Josephoartigasia must have used its incisors for activities other than biting, such as digging in the ground for food, or defending itself from predators," said the study's first author Dr Philip Cox, an anatomist at Hull York Medical School and the University of York.

"This is very similar to how a modern-day elephant uses its tusks."

- Published20 September 2013

- Published12 October 2011

- Published27 March 2014