It must be quite difficult growing up surrounded by professional scientists. Questions tend to get answers that are much more than you bargained for, or worse, receive a question in return. My niece, who is otherwise lovely and intelligent, does have a habit of asking rather unnecessary questions such as "what are you doing?" or "why are you doing that?" in cases where a moment's observation would reveal all. It's probably her version of a conversational opening gambit, so rather than give a straight answer (which, let's admit it, can become rather tiresome), we ask her to come up with her own, tentative answer to the initial question. "Form a hypothesis!" is a frequent refrain when she's about. Then, suitably phrased, we can ask her to test her hypothesis, and the conversation can (not always, of course) take a more enlightening route than it might have done otherwise.

Children are naturally inquisitive (why is that? Form a hypothesis!) and all too frequently one gets a sense that this inquisitive nature is squished by busy parents/teachers/television/websites, rather than being encouraged, nurtured and tuned into a useful way of thinking. A way of thinking, by the way, that turns out to be incredibly rewarding and a great deal of fun. Ignorance might be bliss, but finding out how stuff works and why things are is at least as entertaining – and has great practical value to boot. The scientific way of mind enables you to at least know where to start on figuring things out, as well as equipping you to be a productive, valuable and employable member of society. It also saves you thousands on homoeopathic preparations – you can just drink tap water instead.

Enough propaganda. If scientific thinking is a useful thing to have in your own mental toolkit, if an appreciation of what science can do (and what it can't, as well) is actually inherently attractive and interesting, then why do we do such a bad job of getting people interested? I mean really interested, not in a superficial 'oh wow, pretty colours' fireworks-and-rockets way, but instinctively and deeply fascinated. 'Hooked', if you like. Why, in fact, does this natural, insatiable curiosity turn into acedia, if not outright antipathy?

Form a hypothesis.

I was intrigued, at the beginning of this school year, to see the school diary my daughter brought home. This little book contains lesson plans, homework records, all that kind of stuff that when I was a lad we used to keep on random pieces of paper glued to the back of exercise books or even in our heads. It's a great idea. An even better idea, I thought, is that towards the front of the diary are introductory pages for each subject. They say what you'll be learning, and give a little bit of information about the course.

Here, for example, is History.

This page makes it quite clear that History isn't simply a list of dates and facts (although a timeline is mentioned at the end). It mentions reliability of sources, significance, different interpretation – all the things that I didn't have in my pre-'O' Level course and that made me drop History like a hot cliché.

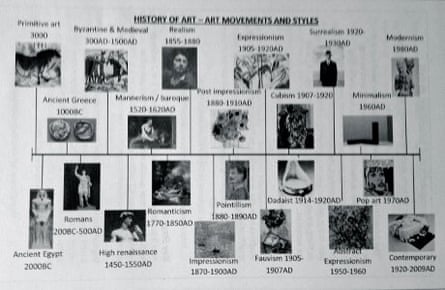

And here's Art.

Sorry about the fuzziness of the photo, but this is brilliant. Look at all those different movements and ways of thinking and representation. Just imagine the range of techniques that must be involved in these two dozen examples. We could even begin to trace origins and influences. The actual course must be brilliant.

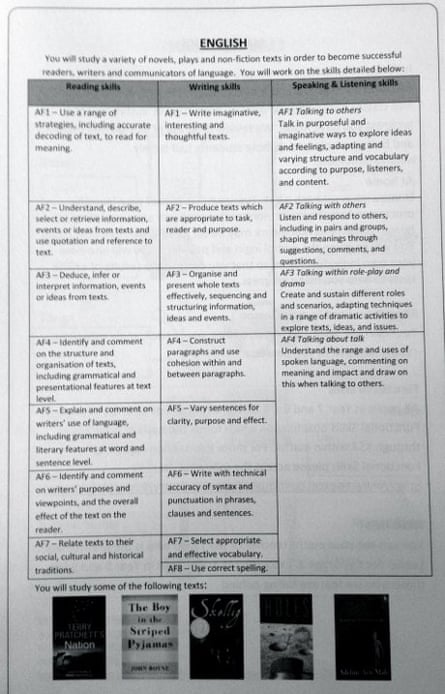

English.

A little more structured and formulaic, but look at this: "Relate texts to their social, cultural and historical traditions"; "Understand the range and uses of spoken language, commenting on meaning and impact and draw on this when talking to others". Amazingly contemporaneous and relevant to life in the South London Republic of Peckham.

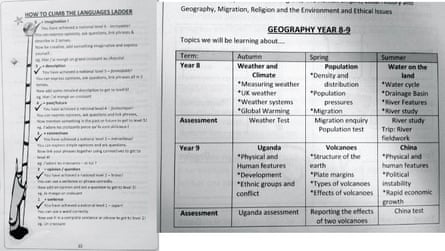

Geography and Languages.

Again, this makes me want to examine the course in much more detail, find out exactly what is going on; it's fascinating stuff.

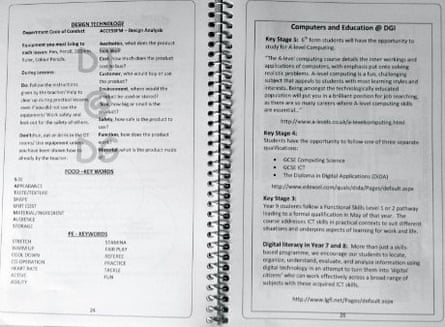

Design Technology and IT.

A little dry, perhaps, but some interesting information about the course, about the skills a pupil might be expected to acquire, even a very brief tutorial on design analysis.

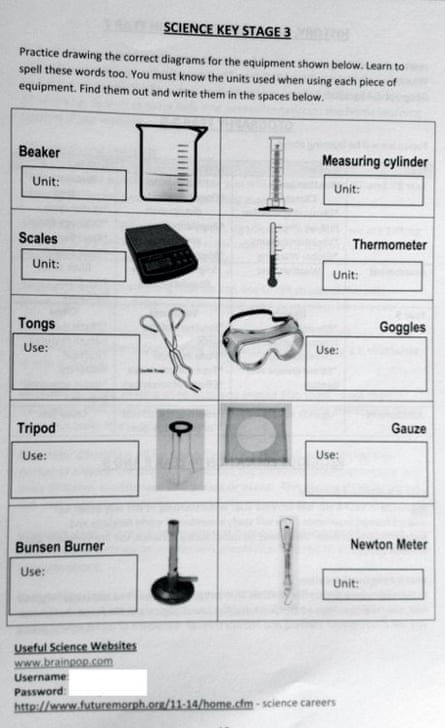

And here's Science.

A list of things to practise drawing. Some rather boring equipment (which no professional scientist I know would ever feel the need to draw) and an instruction to learn units. To be fair, I do not know if Science is still taught as lists of facts and figures to be memorized, but this introduction does far from inspire.

Where is the scientific method? Where is the sense of awe and wonder at the natural world, and a framework for making sense of it all? Where is the opportunity to tinker with the very essence of life itself? Failing that, where is the relevance to my daily life?

Where, to be blunt, is the fun in that?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion