|

|

Have we entered the era of the 1 year sequencer release cycle? *Updated*

Tuesday, January 13, 2015

Illumina's $1000 Genome*

Wednesday, January 15, 2014

A coming of age for PacBio and long read sequencing? #AGBT13

Saturday, February 23, 2013

Next Generation Sequencing rapidly moves from the bench to the bedside #AGBT13

Friday, February 22, 2013

#AGBT day one talks and observations: WES/WGS, kissing snails, Poo bacteria sequencing

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

Got fetal DNA on the brain?

Friday, September 28, 2012

Memes about 'junk DNA' miss the mark on paradigm shifting science

Friday, September 7, 2012

So, you've dropped a cryovial or lost a sample box in your liquid nitrogen container...now what?

Thursday, August 16, 2012

A peril of "Open" science: Premature reporting on the death of #ArsenicLife

Thursday, February 2, 2012

Antineoplastons? You gotta be kidding me!

Thursday, October 27, 2011

YouTube: Just a (PhD) Dream

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Slides - From the Bench to the Blogosphere: Why every lab should be writing a science blog

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Fact Checking AARP: Why soundbytes about shrimp on treadmills and pickle technology are misleading

Monday, October 17, 2011

MHV68: Mouse herpes, not mouth herpes, but just as important

Monday, October 17, 2011

@DonorsChoose update: Pictures of the materials we bought being used!!

Friday, October 14, 2011

Is this supposed to be a feature, @NPGnews ?

Tuesday, October 4, 2011

A dose of batshit crazy: Bachmann would drill in the everglades if elected president

Monday, August 29, 2011

A true day in lab

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

A day in the lab...

Monday, August 8, 2011

University of Iowa holds Science Writing Symposium

Tuesday, April 26, 2011

Sonication success??

Monday, April 18, 2011

Circle of life

Thursday, March 17, 2011

Curing a plague: Cryptocaryon irritans

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

Video: First new fish in 6 months!!

Wednesday, March 2, 2011

The first step is the most important

Thursday, December 30, 2010

Have we really found a stem cell cure for HIV?

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

This paper saved my graduate career

Tuesday, December 14, 2010

Valium or Sex: How do you like your science promotion

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

A wedding pic.

Tuesday, November 16, 2010

To rule by terror

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

Summary Feed: What I would be doing if I wasn't doing science

Wednesday, October 6, 2010

"You have more Hobbies than anyone I know"

Tuesday, October 5, 2010

Hiccupping Hubris

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

A death in the family :(

Monday, September 20, 2010

The new lab fish!

Friday, September 10, 2010

What I wish I knew...Before applying to graduate school

Tuesday, September 7, 2010

Stopping viruses by targeting human proteins

Tuesday, September 7, 2010

|

|

|

|

Brian Krueger, PhD

Columbia University Medical Center

New York NY USA

Brian Krueger is the owner, creator and coder of LabSpaces by night and Next Generation Sequencer by day. He is currently the Director of Genomic Analysis and Technical Operations for the Institute for Genomic Medicine at Columbia University Medical Center. In his blog you will find articles about technology, molecular biology, and editorial comments on the current state of science on the internet.

My posts are presented as opinion and commentary and do not represent the views of LabSpaces Productions, LLC, my employer, or my educational institution.

Please wait while my tweets load

|

|

youtube sequencing genetics technology conference wedding pictures not science contest science promotion outreach internet cheerleaders rock stars lab science tips and tricks chip-seq science politics herpesviruses

|

|

|

|

How AAAS and Science magazine really feel about sexual harassment cases in science

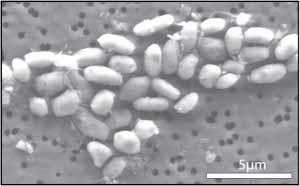

Almost a year and a half ago, NASA ignited a media firestorm after it announced the discovery of a new organism with alien implications. The whole fiasco began when a scientist found a new bacteria in Mono Lake that could grow in the presence of high concentrations of toxic compounds. These types of bacteria are not uncommon on earth. Life seems to find a way to thrive at all extremes and a salty lake in California is no exception to this rule. Researchers have discovered a diversity of life in hot springs, at undersea volcanic vents, and on the cold arctic sea floor. The discovery of this new bacteria; however, was remarkable because the researchers believed that it could use arsenic in the place of phosphate. To the general public, this may sound trivial, but many of the biochemical reactions that provide life require phosphates. The reason why arsenic is so toxic to humans is that it injects itself into all of the processes that use phosphate and prevents those processes from working properly. For example, the molecular backbone that keeps our DNA together is composed of phosphate; the energetic molecules that are produced by the power factories in our cells are composed of phosphate; the specific addition of phosphate to some proteins turns them on or off. Phosphate and its derivatives are essential for life, so to find a bacteria that could function without phosphate and use arsenic in its place was an amazing discovery.

The researchers wrote up their findings and submitted it to the prestigious journal, Science. In a process that now looks ridiculously backwards, the paper was fast tracked through the peer review process, cryptic press releases were written, and a NASA sponsored press conference with all of the bells and whistles was scheduled. The circus that followed can really only be described as a comedy of errors. The press conference and press releases occurred before most scientists were able to access the paper and pore over the actual data. This gave the researchers and NASA a prime opportunity to pat themselves on the back while hoards of “science journalists” jumped at the prospect of being the first to break this miraculous discovery. After the paper was made available to the scientific community, it was clear that the data were completely blown out of proportion. In the zeal of making a landmark discovery, apparently every level of validation in the peer review process was circumvented. Unfortunately, since the peer review process is not open and we do not have access to the reviewer commentary, it’s impossible to say where the system failed. Was it review by unqualified “experts” that led to this mess? Was it a star struck editor trying to impress the boss by landing a landmark discovery for the journal? Who knows, but at this point it’s absolutely clear that instead of rigorously questioning the science, the publishers were throwing champagne parties and planning a public relations superbowl.

And here in lies the problem. In the aftermath of this paper being published, there were cries all across the internet about how science is broken. How could data this bad be published in such a prestigious journal if the scientific system is as robust as scientists claim it is? However, this situation does a much better job of highlighting the disastrous state of scientific publishing and news coverage. Mainstream science reporting is atrocious. It is clear that most people who call themselves “Science Journalists” do not understand how science actually works.

In the case of the arsenic life debacle, the intense criticism that the early release of the paper generated resulted in the publication of 8 technical critiques of the paper being published with the official release of the original paper last summer. These critiques were written by experts in the field and called into question the methods and the conclusions described in the original paper. Two labs took on the task of trying to replicate the original results and their final conclusions were reported this week in the journal Science. Both labs came to essentially the same conclusion: the bacteria discovered in Mono Lake did not use arsenic in the place of phosphate, although it could survive and grow in the presence of high levels of arsenic (which is an interesting result with potential industrial applications).

However, many of the reports on these replication refutations repeat the same tired arguments about the broken scientific system. One journalist goes as far as saying that scientists see replication and cleaning up other researcher’s methods as an inconvenient “pain in the neck.” Really? This situation shows science at its best! This kind of work happens ALL THE TIME in science, it just goes on without media coverage because it’s not easily digestible by the public or “sexy.” Replication and verifying scientific data is one of the most important cornerstones of science, it’s how we know that our results are valid. Another reporter implies that if it weren’t for the heroic efforts of the internet and the blogging community that the arsenic eating bacteria results would have gone unchallenged. Are you kidding me? Seven of the 8 technical commentaries on the original paper were written by people who were not involved in science writing or science blogging. This paper was a HUGE deal in the astrobiology and biochemistry fields. As far as biochemists were concerned, the use of arsenic in the place of phosphate was chemically impossible because it is too unstable. The internet and blogging played a role in the media coverage, but to imply that these data wouldn’t be overturned without internet coverage underscores ignorance of how the scientific process actually works.

Science is not a one discovery sideshow where the results aren’t questioned and are accepted as dogma once a result is published. The system of science is much more complex than that. Scientists rely heavily on previously published research to make further discoveries. Science doesn’t stop once a new result is published, it continues because new results create new questions. Most science is derivative; it relies on previous discoveries to function. Because of this, results are constantly retested in a process called replication. If the original discovery is incorrect, then the further downstream experiments won’t work properly. Science is constantly evolving; old theories are rewritten when new data provides information to overturn them. Science is not static and this is why most scientists understand that they can never use the word “Prove” to describe a result. Science can never prove anything, we can only provide data to support a hypothesis. There’s always a chance that in 100 years, better methods or techniques will be invented that fundamentally change how our results are interpreted.

Although replication is an important part of validating science, one reporter recently stated that researchers find it hard to publish strictly replicative studies, even if the data overturn a previous finding. This is true, but only because strictly replicating an experiment and getting a negative result doesn’t provide any new information. The key is to replicate the finding and then do further experiments to EXPLAIN why the original finding is wrong. Again, this happens all of the time in science. New data is constantly changing and forming theories. This IS the scientific method, it’s not broken, it’s slow but certainly not broken, and it’s only slow because most scientists are careful and rigorous in their execution.

In the end, in the case of the arsenic life debate, it wasn't the internet that saved science, science saved science.

This post has been viewed: 7750 time(s)

|

|

|

|

Jaeson, that's not true at most places. Top tier, sure, but 1100+ should get you past the first filter of most PhD programs in the sciences. . . .Read More

All I can say is that GRE's really do matter at the University of California....I had amazing grades, as well as a Master's degree with stellar grades, government scholarships, publication, confere. . .Read More

Hi Brian, I am certainly interested in both continuity and accuracy of PacBio sequencing. However, I no longer fear the 15% error rate like I first did, because we have more-or-less worked . . .Read More

Great stuff Jeremy! You bring up good points about gaps and bioinformatics. Despite the advances in technology, there is a lot of extra work that goes into assembling a de novo genome on the ba. . .Read More

Brian,I don't know why shatz doesn't appear to be concerned about the accuracy of Pacbio for plant applications. You would have to ask him. We operate in different spaces- shatz is concerned a. . .Read More